4. SKIM THE MANUAL | Intelligent Voluntary Cooperation & Paretotropism

Previous chapter: MEET THE PLAYERS | Value Diversity

Having met our players, with their diversity of values, we can’t rely on aligning them on one grand strategy. Instead, to set civilization up well over the next rounds of play, we must build a playing field that can handle fundamental value differences.

A Manual for Strengthening Civilization

Bob’s Preferences

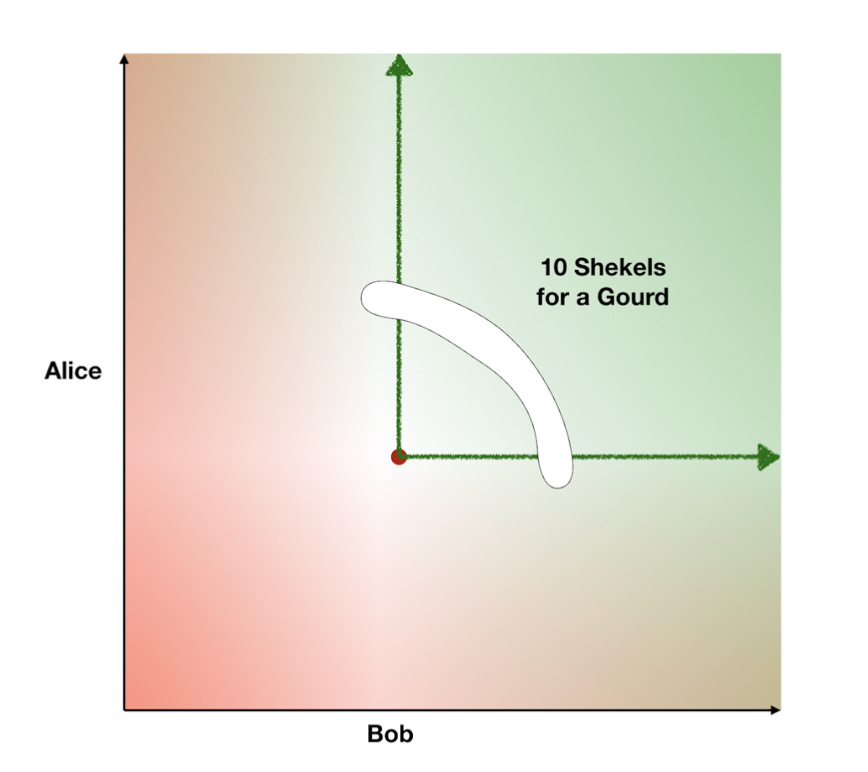

Imagine a game of civilization played by Alice and Bob. A world in which different players have different goals can be described in terms of preferences among future states. The center dot is the current state of the world that players Alice and Bob are in. The axes are the world states, organized by Alice's preferences vertically and by Bob's preferences horizontally. Bob prefers the green worlds to the current world.

Positive Sum & Negative Sum

If we could extrapolate utilities from Alice's preferences and Bob’s preferences, we could say their interactions can lead to outcomes that have greater overall utility or smaller overall utility. Meaningfully comparing utilities across players will become more problematic the more diverse their futures get. But for now, let’s assume everything to the upper right of the red line are “positive sum” outcomes, and everything to the left are “negative sum outcomes”.

Voluntary Cooperation

There is a problem with simply seeking positive sum outcomes. If Bob would be worse off than he currently is, he would fight any attempt to get there. Likewise, Alice would fight the positive sum outcomes she likes less than the status quo. But if Alice and Bob are either equally or better off than they currently are, both have good reason to cooperate. Together, they can move to Pareto-preferred worlds. Situation B is Pareto-preferred to situation A if anyone prefers B to A, and no one prefers A to B. Those worlds can be reached by voluntary cooperation. For human players, we could say these interactions are “freely” consented to; for non-human players, they are simply based on their “internal logic”.

Cooperation Across Humans

Human similarities also come with the tendency to compare oneself to others, including strong fairness intuitions and envy reactions. If Alice’s gain is perceived as too unfair, only she would be invested into bringing about that future, even if, all else equal, Bob would have consented to the deal. The all-too-human tendency to compare ourselves to others may lead Bob to reject a Pareto-preferred deal. It narrows the scope of what the world’s human players can achieve by voluntary cooperation.

Cooperation Across Intelligences

Traditionally, the definition of an agent with utility assumes a comparability that future intelligent systems don't necessarily have going forward. Without meaningful metrics on which to compare utility across very different mind architectures, the diagonal red line, indicating positive and negative sum, disappears.

As long as players have goals and act as though they make choices, they will have revealed preferences. Those revealed preferences may be all we have when designing systems for players to reach their goals. Upholding voluntary cooperation could remain a stable common goal for both Alice and Bob across many rounds of future games, regardless of their intelligence. It’s all they need to unlock Paretotropian worlds that are better for each by their standards.

The rest of this book is about how to set civilization up for this path of intelligent voluntary cooperation. This path contains three components:

1. Upholding Voluntarism

Involuntary Positive Sum

Imagine that Alice, seeking a positive sum arrangement that makes her vastly better off, explains to Bob: “I'll be more better off than you'll be worse off” and embarks on her way to the blue point in the diagram. Bob doesn't like this plan so we have a conflict. Not only do we have a conflict, but Alice expects that there will be this conflict and Bob expects that Alice will expect the conflict.

Hobbesian Traps

In expectation of Alice’s involuntary action, Bob may strike first. Alice, expecting this, will want to weaken Bob first. A cascade of mutually expected conflict can result in a Hobbesian Trap, where the mutual expectation of conflict creates a preemptive conflict. While cooperation is better for both sides, lack of trust or fear of defection can lead to first-strike instabilities, wars, and other terrible games. By reliably upholding voluntary interactions as Schelling Point, and signaling this to Bob, Alice can lessen her and Bob’s incentive to introduce and abuse precedents that could potentially spiral into Hobbesian Traps.

2. Improving Cooperation

Single Anonymous Interaction

Today’s world of cooperation is complex and involves anonymous situations where neither reputation nor contracts can grip. In situations where all players jointly prefer an outcome, but cannot get there by only interacting voluntarily, an obstacle is obstructing their path to Pareto-preferred worlds. To cross the obstacle, we need better tools for cooperation.

Imagine Bob gave Anonymous Alice 10 shekels for the promise of a Gourd. She is 10 shekels richer and he is 10 shekels poorer. Anonymous Alice would no longer have a reason to give Bob what he wants. Upon Bob inquiring where his Gourd is, Anonymous Alice may run off, quoting Hobbes, “For he that performed first has no assurance the other will perform after, because the bonds of words are too weak”. Bob, knowing this, would never give Alice the 10 shekels in the first place. What if Bob could lock up his 10 shekels in escrow that automatically pays Anonymous Alice when she proves that she has delivered the Gourd?

Improving Technologies of Cooperation

A tremendous number of remaining problems are basically the same phenomenon writ large. If all Alices and Bobs in this world could find each other, they may be able to build bridges to Pareto-preferred worlds. In reality, collective action dilemmas are often phenomena in which 1000s, or millions of players interact simultaneously. Rather than being simple trades, they might be complex arrangements that unfold over time. Players can’t get to preferred worlds in a way that ensures all are better off at each step along the way. To tackle these problems, we need to innovate in technologies of cooperation and democratize their use.

3. Intelligizing Voluntary Cooperation

Civilization as Diagram with 7 Billion Dimensions

When considering Alice and Bob, we need to remember that we’re actually looking at a 7+ billion dimensional diagram. Any particular interaction involves only a bounded set of aspects of the world and only a bounded number of participants. For each one of these interactions, there is a separate diagram, in which we can organize the possible states of the world.

Voluntary Independence

Imagine Carol and Dave are in some other part of the world. They have never heard of Alice and Bob, who have never heard of Carol and Dave. Let's rotate Bob out of the diagram and rotate Carol in. In parallel to Alice’s and Bob’s interaction, Carol is cooperating with Dave to bring about a world state in which Carol is better off. Even though each of these individual transitions hug the edges of the Pareto-box, collectively, they are taking orthogonal steps into the Pareto-preferred area.

In order for the right to choose to cooperate to be meaningful, we need the right to choose not to cooperate. Voluntary independence is actually most of the 7+ billion dimensional diagram. Most people don't know each other and most of their activities have no strong connection to most other activities in the world.

Thanks to the independence of the arrangements that form in a vast experimentation space, some arrangements can go forward when others get stuck. The system continuously selects for arrangements that create productive cooperation such that it is dominated by their beneficial results. While we should improve our arrangements, this process is about becoming better at aligning everyone’s expectations of increasing payoffs by actually increasing payoffs.

Strengthening Civilization’s Paretotropism

Plants have a phototropism, in that they grow toward the light. Civilization has no goals of its own. But it does have a dynamic, a paretotropism: In the same way that plants grow toward the light, civilization, emerging from our voluntary interactions with each other, progresses towards worlds that are generally better for everyone. By cooperating via voluntary choices, and otherwise leaving each other alone for voluntary independence, our civilization is climbing Pareto-preferred hills.

To continue on this trajectory in the future, we need to find to extend the architecture of voluntary cooperation that has emerged among humans to other intelligences which will soon dominate the playing field.

Intelligent voluntary cooperation relies on respecting the boundaries of other entities such that their reaction is based on their internal logic. For humans, we have long-evolved norms around respecting our corporeal boundaries. In today’s object-oriented programming, specialized computing entities are encapsulated so one object cannot tamper with another’s contents. Such existing examples of boundaries may provide useful guidance when designing the cooperation architectures for the next rounds ahead. Successfully integrated into our fabric of voluntary request making, new intelligences have the potential to turbocharge the paretotropism of our civilization.

Intelligent Voluntary Cooperation: The Real World

Having looked at a manual for intelligent voluntary cooperation, let’s see how the strategy works in the real world and which lessons to apply in the game ahead.

1. Upholding Voluntarism

The Game So Far: Voluntary Schelling Points Emerge

How has voluntarism shaped our civilizational game? Data on prehistoric societies suggests that our ancestors lived with extraordinarily awful rates of violence.1 Since then, violent deaths have decreased, first relative to population size, and more recently in absolute numbers. Major powers have not fought a physical war in a while, and while there are more civil conflicts, they bring fewer deaths.2

The decline in violence hasn’t been perfect but it has gradually shifted the balance of our interactions from involuntary interactions towards voluntary ones. We increasingly have the freedom to say no to interactions without being forced into them.

With cooperation becoming a better strategy than violence to achieve our goals, it became beneficial to understand other peoples' goals so we can offer them cooperation opportunities.3 If I need money, and want to sell you a product you want, it pays if I can imagine what kind of product you would enjoy. Effective cooperation, such as in commerce, involves creating situations in which others serving our goals also serves theirs. The instrumental goal of cooperating evolved into the felt goal of caring about others' goals, i.e. empathy. Global mass media may have helped extend our empathy by increasing our ability to put ourselves in the shoes of strangers. Seeing each other as fellow humans, rather than dangerous outsiders, further reduces the impetus for violence.4

Think of one of the many bloody territorial wars across history. Often, not even victors come out net positive. All players have an interest in avoiding such costly struggles. All sides should want to find a point of mutual agreement without anyone feeling they’ve made too much of a concession. If they can agree a disputed territory has an obvious geographic marking, this common-knowledge landmark could be a good point to settle on. The river can serve as Schelling Point for coordination.

Thomas Schelling pioneered the idea that even without communication, we can often cooperate by converging on a focal point which we mutually expect to have prominence for the other.5 This is why many territorial boundaries are a mountain range or a river.

We find a similar situation in American politics today. Political factions are increasingly polarized, and neither side finds the U.S. Constitution to be an ideal document for advancing their cause. All parties have some interest in a Constitutional Convention to rewrite the Constitution to exactly serve their purposes. However, all parties are terrified of risking a Constitutional Convention, and we should expect strong lobbying against it. The potential outcome is sufficiently risky that, while the current framework is not ideal for any party, it is better than what they might end up being forced to accept. The U.S. Constitution is stable because all players recognize that the prospect of its instability is more frightening than living with what we now have.

Just as the river serves as a territorial Schelling Point, and the Constitution serves as a Schelling Point for U.S. governance, voluntarism is increasingly becoming a Schelling Point for our civilization. We all tend to gain by cooperating with each other and the more we rely on these dynamics to achieve our goals, the more we create feedback that keeps pushing the rules in that direction. Even if you find it is in your occasional interest to engage in involuntary interactions, your overall interest may well be to uphold the voluntary system if you expect to benefit from it. Weaker norms might better enable you to cheat but they also better enable everyone else to do so. The overall system is less likely to serve your own interests.

To the extent that we make exceptions for ourselves to rely on involuntary means when interacting with others, we establish precedents for interactions that overpower some players by non-agreed upon means.6 When voluntary Schelling Points are lost, we can spiral into Hobbesian traps, in which the mutual expectation of involuntary action leads to pre-emptive conflict.

Since the first strike instability during the Cold War we know that such traps can bring us to the brink of destroying the world.7 World War I with its entrenched warfare situation was another trap in which both sides were suffering tremendously, but neither knew how to get out of the situation. We must avoid Hobbesian Traps at all costs.

The Game Ahead: Multipolarity & Compensating Dynamics

Multipolarity: More Like Natural Language, Less Like Governments

The more players uphold voluntary interactions as Schelling Point, the more we can rely on it. Unipolar systems with a single dominant actor can arbitrarily breach voluntarism without fearing feedback. Power is diminished when divided, and so is the power to engage in involuntary interactions. Multipolar systems can keep each other in check.

Take natural language as the ideal example of a voluntary system emerging from multipolar interaction. Historically, there was no understanding of the hard difference between the concepts of heat and temperature, or mass and weight.8 Instead, there was a cloud of words that sort of meant the same vague cloud of meanings. When people tried to reason precisely about this heat and temperature cloud of meaning, they were wrapped up in intellectual knots.9 Distinguishing between heat and temperature, allowed people to pick words from these clouds to nucleate them into different sounds of a newly explained concept. Sometimes it goes the other way, and concepts thought unrelated suddenly become connected. For instance, “entropy” is a synthesis of signals from engineering and thermodynamics.

The coherence of natural language does not emerge from the top-down decision of an authoritative governance structure. Instead, it is a continuous re-negotiation with words as Schelling Points for meaning.10 The evolution of words has both a drive to coherence, where we mean the same thing, and sudden switching events, as we discover new concepts, create new coinages, vocabulary and jargon. Language is a beautiful, spontaneous order that emerges from the interaction of many players under the incentive of wanting to be understood by each other.11

If language is a good example of extreme decentralization, markets are in an intermediate category. They don’t have decision-making power for the overall system but neither do they emerge only from individuals contracting directly with each other. Corporations are the dominant entities. They have internal centralized decision-making powers coexisting with a lot of bottom-up activity, and are themselves embedded within a multipolar world of markets. While individual large corporations are often seen to have a degree of agency, their overall market activity is still emergent through many parties interacting to try to influence the process.

Let’s go up one layer of centralization to governments. In the U.S., power is decentralized in multiple instances via the Constitution. First, the Founding Fathers left most power in the hands of individuals and didn't centralize it in government. Second, they left most of the remaining governmental power to the states, not the federal government. Finally, the federal government power was divided among the legislative, judicial, and executive branches, and restricted via the Bill of Rights constitutional amendments. The founders were not confident this balance would be stable and there is no guarantee it will be. Today, we see formerly-decentralized decisions being gradually transferred from the states to the federal level.

If we want cooperative partners to bring their local knowledge to bear and keep each other in check, any arrangement that can be more decentralized should be. This is embodied in the subsidiarity principle; when seeking to come to joint decisions, we should do so at the smallest scale necessary for a decision. Subsidiarity would not only favor decentralizing decisions to the state level instead of national level. It also means strengthening the cities’ role where most of us directly experience decision consequences. Within cities, subsidiarity would encourage decisions at the fine-grained local community level with fluid processes and reciprocity.

A move away from dominant hierarchies can be very beneficial. Robert Sapolsky shows how, in a baboon troop in which dominant violent males died due to an accident, the lower-ranking baboons, rather than reassembling traditional hierarchical pathologies, remained more peaceful and cooperative over the long-run.12 If baboons can do it, human players should be able to. The more we use multipolar interaction architectures (like languages) and less unipolar ones (like governments), the more we can rely on each other to uphold systems of voluntary cooperation.13

Compensating Dynamics: From Peace of Westphalia to Crypto Nations

History shows we can work against strong pressures to centralize. The Peace of Westphalia stopped the notoriously bloody thirty year religious war in Europe. Each warring state sought to involuntarily impose their values onto the other side.14 All parties paid huge costs for following their own perceived best course of action. Finally, in 1648, they negotiated a peace allowing each nation to determine religious practices on their side of the boundary with little interference. Spain and France were assigned the role of guarantor powers that were, by treaty, obligated to defend the constitution of the Holy Roman Empire. They could be called upon by anyone injured according to the Peace. Instead of just providing friction against power centralization, it introduced a feedback loop that actively corrected and pulled the system away from centralization.

The Peace of Westphalia lasted for centuries and it is sometimes regarded as one of the first applications of the collective security principle in International Relations.15 In a collective security arrangement, “each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats to, and breaches to peace”. When one state in a pact gains power that threatens the peace, other states cooperate collectively against them. The actions of the rest restore the balance and provide security for all.

What is preferred to withstanding centralization? Actively self-correcting for it. If we realize early that part of an arrangement becomes a threat, a coalition of powers can proactively cooperate to restore equilibrium. In a system in which participants understand it is in their interests to preserve peaceful multipolarity, self-correcting dynamics can be built in. This is more than a system of “robust multipolarity”, where multiple players keep each other in check by watching each other. Systems in which participants cooperate to compensate for power grabs can create an “antifragile multipolarity” that gets stronger under stress.

Charter cities and seasteading ambitions seek to create meatspace alternatives to national players. Cyberspace offers another arena to compensate for state power through the creation of transnational communities that are entirely voluntary. It has an almost perfect realization of a neutral simple rules framework to experiment with.16 Some already use this to prototype new forms of self-government in virtual communities, which increasingly become the realm in which we uphold each other’s rights.17 One day, crypto nations and network states, such as 1729, may allow their members to collectively negotiate with existing legal jurisdictions, expanding compensating powers from the digital to the physical world.18

Balaji Srinivasan popularized the idea of actualizing digital communities into the physical world through network states. Watch his Intelligent Cooperation seminar.

2. Improving Cooperation

The Game So Far: Rights, Contracts, Prices, and Institutions

How did we get from a civilization based on voluntary interactions to today’s sophisticated ways of cooperating, including property rights, contracts, and prices? Civilization is made up of many players pursuing many goals. Many of these plans make use of resources which are scarce. To pursue our goals, we had to gradually learn how to coordinate around a limited amount of resources. Property rights solve this problem. They confer the rights to things, which really is a proxy for the rights to do things. At first, a simple theory of accounting sufficed. Alice could tell her neighbor, Bob: “this cow is mine if it is on my property. In exchange for some fruits, I make it yours by moving it to your property”.

But human beings are linguistic creatures, so rights about physical goods could be repackaged to more abstract arrangements. The transferability of physical goods created a model in our minds of what it means for something to be property. Once we had this notion, we could take less literally physical items, declare them to be property, and create abstract arrangements such as contracts to manipulate them. Thousands of years of the evolution of human institutions have given us technologies of commitment, such as reputation and contracts, to bind ourselves to mutually preferred agreements.19 Alice could tell Bob: “give me your fruits now and I promise to give you my cow tomorrow”.

Pairwise barter deals where one good is exchanged for another for mutual benefit are hard to find and leave lots of value on the table. Because continuing to be a participant in a particular contract is itself valuable, that right can be treated as property for other contracts again. Bob could tell his neighbor Carole: “give me your grains, and you’ll get Alice’s cow when I get it in exchange for my fruits”.

Such large multi-way deals would yield the full benefit of trade, but are difficult to negotiate. Currency allows the equivalent of multi-way deals via separate pair-wise trades. Prices can represent a summary of individual valuations of a good, the demanders’ use values and the suppliers’ costs. Instead of running back and forth between Alice and Carole, Bob can pay for the promise of Alice’s cow and use that currency to buy Carole’s grains.20

Via contracts, institutions for manipulating rights evolved that allow more parties to cooperate creatively. Gradually, markets emerged around the transferability of rights. By recognizing the contract participation right as property other contracts can use, we enable networks of contracts composed of contracts. This dynamic of higher order composition gave rise to today’s complex cooperation ecosystem. These arrangements were possible only by building more abstract arrangements from within a working system. Now we can reinvent them.

The Game Ahead: Polycentrism and Out-Competing

Forging Polycentric Bonds: Open Source

A minimal set of voluntarism can lay the groundwork for constructing and joining cooperative arrangements with very complex rule sets.21 For instance, for managing common streams in the Swiss Valais, everyone in the community has a right to take from the stream, in return for a few days of maintenance work each year. These Swiss communities are small with high reciprocity and access control in the form of mountains.22 In civilization at large, we cannot casually eject people, so we find small-scale commons within larger scale units, with arrangements cutting across both. Having multiple poles of decision making that are independent of each other is often called “polycentrism”.23 Elinor Ostrom pioneered the concept by showing that it can help solve various collective action problems.

But new cooperative arrangements come with their own pathologies, incentivizing people in unforeseen ways. Take today’s corporations as an example. A corporation has few ways to create an internal project with the guarantee that it won’t be canceled by its management. There are almost no formal means within the corporate governing structure and, if promised informally, there is no way of holding the company to it. Management can change their minds, and they seldom can deny themselves the right to do so. In response, many projects form as a collaboration between employees in multiple companies who use contracts to make credible commitments. Each of them think it is now much more credible that the project will stick around.

Open source is an extreme case; if the company kills it, you can leave the company and continue working on it. Prior to open source, talented technologists have repeatedly put some of their best intellectual effort into a proprietary project that was canceled. They realized that projects which they were willing to start under those conditions weren’t the ones worth starting. With open source, companies can make a credible promise to the employees that they can keep working on a project even if the company loses interest. In turn, talented employees pour their heart and soul into the project.24 Making binding promises is an important means of cooperating. Rather than imposing a simple top-down model that makes this difficult, cooperative arrangements like open source cut across different circles.

By joining different hierarchies in a variety of cross-cutting circles, we can compensate against arbitrary power in any one of them.25 Being part of overlapping communities is more manageable for our tendency to compare ourselves to our peers: Bob may be less affected by the grandiosity of Alice’s Dyson Sphere, when his wildlife spotter fan club praises him for preserving a pristine Platypus specimen.26 If you can seek social worth through different roles in different circles, violence may be less common than if all of your self-worth depends on one pecking order. So even if it can’t solve all collective action problems, polycentrism has other benefits by making it easier to engage in binding commitments, and harder to engage in involuntary actions.

Out-Competing Sub-Optimal Institutions: Education

Every sub-optimality in our civilization should be an invitation to innovate—without upsetting voluntary Schelling Boundaries. Let's take education as a collective action problem. Scott Alexander diagnoses that “students’ incentive is to go to the most prestigious college they can get into so employers will hire them—whether or not they learn anything. Employers’ incentive is to get students from the most prestigious college they can so that they can defend their decision to their boss if it goes wrong—whether or not the college provides value added. And colleges’ incentive is to do whatever it takes to get more prestige —whether or not it helps students.”27

When noticing an apparently maladaptive feature which has been part of a society growing and increasing in wealth and knowledge, let’s first stop and consider alternative functions. This avoids tearing down Chesterton’s Fence, the canonical example of a feature with an important function not understood by those seeking to remove it.28

American education is undoubtedly in a sub-optimal state. Nevertheless, the U.S. university system is still where most of the world is eager to send their students. Much of the U.S.' actual knowledge growth has made use of its system of teaching and research, even if not in the ways we commonly think. Part of good universities’ attraction is prestige and trademarking.29 Even if a good school teaches a student nothing, graduating from one whose entrance criteria are predictors of intelligence is a signal. Especially since students from good schools spend years socializing with other students who went through the same filter. They received some education and a network whether their knowledge was actually increased by their classes or not.

While these are not official university functions, at least trademarks are not completely random. Noticing this divergence between claimed and delivered benefits is an innovation opportunity. The Thiel Fellowship has convinced high-potential students at good universities to join a prestigious entrepreneurial program instead. Having been accepted to the university first, they can still use this as a signal. This works so well in Silicon Valley that “dropping out” is becoming a positive signal itself.30

Rather than rolling back evolved institutions, newly created systems can out-compete existing ones. Until we innovate by deploying our insight in the real world, we don’t know in how many ways it is wrong. If we underestimated how good the existing institutions were for reasons we didn’t understand, then it is good that our attempts to supersede them using voluntary cooperation failed. We want those attempts to fail.

Even if we don’t solve a particular collective action problem via voluntary means, at least we are making poor choices among Pareto-preferred paths. If instead we could destroy institutions we didn’t appreciate by something more forceful than voluntary cooperation, we risk destroying hard-gained value, perhaps irrevocably so, and open up the door to Hobbesian Traps. Given what’s at stake in civilization, our goal needs to be depessimizing, not optimizing.31

Curious for more? Check out Price Discovery in Markets & Civilizational Progress.

3. Intelligizing Voluntary Cooperation

The Game So Far: Civilization Serves Our Interests

From our vantage point, it’s hard to wrap our head around the many wonderful developments that got us where we are today. Circa 1820, nine in ten people on the planet lived on less than $1.90 per day. In 2015, this was only around one in ten. As the population increased, at first, only the ratio of people in extreme poverty fell. But more recently, the actual absolute number of people in poverty is plummeting faster and faster while our overall population continues to grow.32

We are making progress on so many fronts. Modern hygiene, better nutrition and medicinal advances means fewer children die of starvation and the elderly can rejoice in living healthier lives.33 We are rapidly becoming more educated; not only are more kids attending school for longer, but in most countries, almost the entire population is literate now.34 Countless other achievements could be added, such as greater personal autonomy and fun, or improved communication and travel.35

Recently, obstacles to our ascent have become more apparent. Some worry that the rate of scientific progress is slowing down, and we are entering a “great stagnation”.36 Others worry that even as technology and productivity improve, prices are rising in areas such as healthcare and education.37 While - thanks to a mix of competition and digitalization - key air pollutants, such as sulfur dioxide, are in decline, pollution continues to harm health and livelihoods, displacing humans and other species.38 Technological progress coupled with increasingly global reach also means increasing the potential reach of technologies’ violent uses.39 Those are tricky problems. Nevertheless, in broad strokes, civilization has been rapidly getting better at serving our interests.

If you’re surprised to hear this, you’re not alone. A 2016 poll found only eight in a hundred U.S. residents knew that global poverty declined in the previous 20 years.40 No wonder; it’s hard to appreciate how incremental positive developments add up across history. You weren’t alive yet when, in 1900, almost half of US households had more than one occupant per room, only every fourth household had running water, and only six in one hundred kids graduated high school. Since then, U.S. living standards have increased at least five-fold.41

But expectations adjust, and the remaining brutal aspects of everyday interactions stand out. Scott Alexander captures this sentiment well: “Fit companies—defined as those that make the customer want to buy from them—survive, expand, and inspire future efforts, and unfit companies—defined as those no one wants to buy from—go bankrupt and die out along with their company DNA. The reasons Nature is red in tooth and claw are the same reasons the market is ruthless and exploitative.”42

If this sounds intuitive, consider an alternative perspective. Zooming in on evolution shows the differences between today’s civilization and nature’s predatory principles: “To survive, animals must eat animals or plants; this happens most often through predation. Producers, unlike prey, will voluntarily seek out those who want to consume what they have, using advertising, distribution networks, and so forth. Consumers, less surprisingly, will seek out producers [...] by reading advertising, traveling to stores, and so forth. The symbiotic nature of this interaction is shown by the interest each side has in facilitating it.[…]In human markets (as in idealized markets) producers within an industry compete, but chains of symbiotic trade connect industry to industry.” 43

In today’s civilization, competitors compete at better cooperating with the rest of the world. While competition is the norm within industries, chains of symbiotic trade are the norm across them. But we tend to find uncommon phenomena interesting and common phenomena boring, and so focus on unusual predatory behavior and crime over boring symbiosis in trade and markets.

This tendency, let’s call it an outlier inversion, is amplified by the media reporting on interesting cases of crime and embezzlement rather than on positive trends, such as the daily massive satisfactory turnover of goods. When pointing out how far we still have to go, we can start with appreciating that we’ve come a long way. Progress occurs even when unnoticed. But noticing it seems an important first step towards accelerating it.44

The crucial thing in common is that our achievements are attractive from many perspectives, regardless of what one values and which goals one pursues: Longer lives provide more time to pursue goals, improved health provides more energy to do so, and better education and more freedom improve one’s chances of achieving them.45 Gradually and imperfectly, civilization is climbing Pareto-preferred hills: “If pairwise barter amounts to Pareto-hill-climbing across a rough terrain with few available moves; trade in a system with currency and prices amounts to hill-climbing across a smoother terrain with many available moves”.46 Tyler Cowen compares our modern civilization with a Crusonia plant, a mythical automatically-growing crop that generates more output each period. The more crops, the more there is to go around for different players to pursue their goals.

Listen to Tyler Cowen’s seminar on civilization progress and stumbling blocks.

The Game Ahead: Boundaries and Composition

Set Voluntary Boundaries: Institutions & Computers

The evolution of complex institutions starts with our need to create plans in ignorance of the plans other players are creating. Rather than incentivization alone, a main bottleneck for civilization is coordination around limitations of knowledge. Even if we all wanted to maximally cooperate with each other, we would still mostly be ignorant about how best to do this. Cooperation brings local knowledge to bear for intelligent problem-solving:

If you want to have a package delivered, you walk into a post office, hand the clerk on the other side of the counter a package, tell her where it should go, give her the money, and the package is delivered to its specified destination. The clerk does not need specialized knowledge that you are sending your father a birthday present. Likewise, the package delivery service knows about trucks, airplanes, schedules, and barcodes that you don’t need to know. A lot of specialized knowledge on each side is abstracted through the common interface of a package delivery service.47

The package delivery service functions as an abstraction boundary over two variable factors; why someone wants to deliver a package and the multiple means to deliver it. It can convert specific relationships into abstract relationships, and each side’s local knowledge can be composed into more complex problem-solving abilities. In addition to traditional institutions, we rely heavily on these less formal day-to-day institutions to cooperate.48 When such successful templates for cooperation emerge, they reduce the costs of reusing working solutions. We can draw on ever wider range of knowledge without having to acquire it ourselves.

The benefit of composing local knowledge into more intelligent systems is only too familiar to software engineers: In the early days of software engineering, they realized big problems need to be broken down into smaller ones and the plans to solve them. But if each plan can draw on any program resources, any memory address, any bit of data, etc., the result is a massive interference problem that creates bugs everywhere.49 Knowledge locality in the face of plan complexity created a reliance on specialized objects. By dividing resources into portions which can have separately held rights, we can formulate parts of the plan in confidence it can unfold without arbitrary interference from other plans using those same resources.

Complicated programs are broken down into simpler objects that engineers know how to build. Networks of objects communicate to exchange information. The information carried by each object is encapsulated so one object cannot tamper with another’s contents. These boundaries create independence across objects but also allow for them to be composed into architectures of cooperation. When the request-maker sends its request, the recipient responds only according to its internal logic. Via such voluntary request-making, separate objects can solve a small component of a problem, and combine their knowledge into much greater problem-solving ability.

Composability is key in this process. In foundational mathematics, a predicate operating on numbers is a first order predicate, while a predicate that operates on first order predicates is a second order predicate. Unlike in foundational mathematics, in programming, higher order predicates don’t have to have a particular place in the order of predicates. They can just operate on higher order predicates without restriction or stratification. This lets us build abstraction layers on top of abstraction layers, which can both manipulate objects and be manipulated by objects. It’s thanks to this generic paramaterizability that we can build increasingly complex ecosystems of objects manipulating other objects.

Compose Local Knowledge: Markets & APIs

Object-oriented programming and human cooperative systems have many parallels. Similar to rights that can get composed via contracts into ever richer cooperative agreements, networks of computational entities can be composed into richer computation. The package delivery service with a structure of ritualistic interaction is similar to an API in object-oriented programming. Its primary function is to enable us to coordinate, despite our ignorance of all the specialties taken into account by the other side of that counter. This is similar to how an API coordinates sub-programs with specialized knowledge and composes them into an overall system with better problem-solving abilities.

In both cases, the bottleneck is not conflict of interest but the locality of knowledge. Just as the package clerk and you want to cooperate but need the postal service abstraction boundary to find out how, in object-oriented programming, abstract interfaces (APIs) explain how concrete objects can make requests of other concrete objects across abstraction boundaries. Well-designed systems compose local knowledge. By creating boundaries between request-making and request-receiving sides, selection pressures can operate on both sides. As systems adapt and grow, local knowledge is composed in more intelligent ways.

This applies to primitive computer systems that utilize more knowledge than any one of the sub-components could, to systems that we can start to call intelligent, to market processes, institutions, and large scale human organizations, up to our entire civilization.

Increase Civilization’s Superintelligence: Economic Computation

Civilization is a network of entities with specialized knowledge, making requests of entities with different specializations. Just as object oriented programming creates an intelligent system by coordinating its member specialists, our institutions evolved to increase civilization’s adaptive intelligence by coordinating its member intelligences. We are essentially the objects within human society’s problem-solving machine, which takes into account vastly more knowledge than any one of us could possibly possess.50

To illustrate this point, Leonard Read traces back a pencil’s development process, from tree through production line to coloring to final product. While no one person knows how to make a pencil and most of the thousands of people involved in producing it don’t know of each other, live in different countries, speak different languages, they nevertheless cooperate to produce a pencil, one of the thousands of items we take for granted in our lives. Friedrich Hayek summed up this dynamic as “civilization begins when the individual in the pursuit of his ends can make use of more knowledge than he has himself acquired.”51

The shared parallels between human and computing systems was appreciated by influential computer programmers in the field; Bertrand Meyer relied on the concept of interfaces as contracts52, Alan Kay explained his approach to computing in terms of machines talking to each other,53 and Carl Hewitt was very much inspired by Karl Popper’s idea of how knowledge composition in the scientific community works.54 The Agoric papers sum up that “like all systems involving goals, resources, and actions, computation can be viewed in economic terms”.

If computing approaches inspired by human cooperation helped unlock many of today’s software engineering successes, they are a good start for building future human and computer arrangements. Once we improve cooperation across individual humans, we can scale it further down to individual computational processes and objects. We should expect market responsiveness to move further down into the automated objects interacting with both each other and ourselves. It is hard to imagine what is possible when we redesign system rules from the perspective of being objects inside the system. We can already guess the next levels of the game will reproduce composability of human commerce.

Chapter Summary

When we play the game of civilization within a framework of simple rules, interesting patterns emerge. Today’s market economy is such a pattern, emergent from rights and contracts constructing the rules of the game. The historical decline of violence shifts interactions to voluntary ones that tend to serve the player's goals. Over time, civilization is becoming more intelligent by developing abstraction boundaries—from APIs to institutions—that coordinate local knowledge into an astounding problem-solving ability. Civilization becomes increasingly superintelligent and aligned with our interests. By exploring and reinventing the underlying rules from within the game, we can unlock new levels of cooperation.

Next chapter: IMPROVE COOPERATION | Info, Money, New Rights to Do Things

Some analyses, such as Max Roser’s War and Violence show that the percentages of individuals killed by violence range from about 60% to less than 5% in both prehistoric and nonstate societies. While a large range, in 2007 just 0.04% of deaths in the world were from international violence. This suggests our 2007 world was at least an order of magnitude safer than most prehistoric societies.

See Max Roser’s Battle-related Deaths in State-based Conflicts and Steven Pinker’s Better Angels of Our Nature, in which he defines the +70 years of peace since WWII as the “Long Peace”. Some scholars, such as Cirillo and Taleb in What Are the Chances of a Third World War, worry that the "Long Peace'' may merely be a gap between major wars, since they seem to occur once a century.

Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker.

The human felt sense of empathy is useful but not necessary for cooperation. We just need a framework in which future entities interact that leads them to cooperation to make them better off. Perhaps future entities will have the cognitive capacity to pursue the instrumental goal of cooperation without constructing an extended sense of empathy.

See Thomas Schelling’s The Strategy of Conflict. To see how, imagine the Split Money Game in which you and another player have to share $100. You are not allowed to communicate but have to write down how much you claim. If your claims add up to $100 or less, both of you get their specified amount. If the sum is higher than $100, both of you get nothing. What would you choose? Chances are you choose $50. Why? Because you can reasonably expect it to be a unique focal point for the other players.

For instance, the 1976 exception allowing the US government to override citizens’ rights in a state of emergency resulted in 35 active emergencies in 2020, each renewed annually by the president. There are exemptions that warrant a breach of voluntarism. Nevertheless, for any state in which an involuntary action could lead to a Pareto-preferred world, it is often possible that an alternative action can bring it about voluntarily. Taking Children Seriously, a child-education philosophy, holds that it is possible to raise even children, often treated as agents incapable of consent, without doing things against their will. Instead, “parents and children work to find a solution all parties genuinely prefer to all other candidate solutions they can think of”. Finding common preferences can be hard but where they are found, there is no coercion that can spiral into Hobbesian Traps.

Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg.

When Heat and Temperature Were One by Marianne Wiser and Susann Carey.

Mark S. Miller’s work on access control, discussed in Chapter 7, is based on a similar intention to disambiguate “permission” versus “authority”.

In The Meaning of Centralization Vitalik Buterin points out that, even though they try, in the binding of words to meanings, no decision-making organization controls how people actually choose to speak.

Language, Cognition, and Human Nature by Steven Pinker.

Sam Butler proposes the more granular distinction with natural language, followed by markets, followed by the Swiss federation, followed by US federalism, followed by Oligarchy/Plutocracy, followed by Monarchy/Dictatorship.

See Henry Kissinger’s World Order.

See Wikipedia’s Collective Security.

See Mark Miller’s Computer Security as the Future of Law.

See Chip Morningstar’s The Lessons of LucasFilm’s Habitat.

See Robert Axelrod’s The Evolution of Cooperation.

Adam Smith’s Theory of Value by Vernon Smith.

See Robert Nozick’s Anarchy, State, Utopia.

See Elinor Ostrom’s Governing the Commons.

See Elinor Ostrom’s Beyond Markets and States.

With the transition to remote virtual work, the nature of work is becoming more polycentric. With physical travel to an office, you can only be in one place at a time. Whereas if you're working from home over videoconference, there is no such exclusivity constraint. The normal employment relationship may move to multiple jobs for multiple organizations, blurring the circles of employment and independent consulting, and with that their hierarchies with various kinds of rewards.

See Gwern’s The Melancholy of Subculture Society.

Virtual communities may also help curb polarization because people are less likely to encounter random extreme positions of the out-group in the wild but may gradually get to know pieces of it through overlapping communities.

See Scott Alexander’s Meditations on Moloch.

In The Thing, Gilbert K. Chesterton introduces this principle by analogizing institutions with a fence erected across land: “The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, 'I don't see the use of this; let us clear it away.' To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: 'If you don't see the use of it, I certainly won't let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

See Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler’s Elephant in the Brain.

Próspera in Honduras is a nascent charter city experimenting with 3D property rights, modular construction of homes, common law regulatory options, and education and healthcare options patchworked from successful countries. The Nevada state government is considering legislation that would let companies form “Innovation Zones” with county-level governmental powers.

Nassim Taleb’s term ‘antifragile’, introduced in Antifragile, describes systems that grow stronger under pressure rather than just being resilient to pressure. The question we will address in future chapters is about our system’s proclivity for disaster. We expect antifragile systems also to be less prone to disaster. But there may be other systems that don’t grow as strong under pressure but are also less prone to complete disaster. In that case, we may have to be content with such a robust system, even if it is not antifragile.

For instance, in Global Extreme Poverty, Max Roser compares absolute numbers of poverty between the early 1980s and 2015: From 2 billion people, they dropped to 735 million people living in extreme poverty.

How Did Life Expectancy Change over Time? by Max Roser.

See Global Literacy by Age and Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now.

See Tyler Cowen’s Stubborn Attachments and Matt Ridley’s Rational Optimist.

In The Great Stagnation, Tyler Cowen suggests progress is unevenly distributed over time. While it has been in a slow period of late, we should do our best to help new technological developments to speed it back up. See Patrick Collinson and Michael Nielsen’s Science is Getting Less for Its Buck.

In Why Are the Prices so Damn High?, Tabarrok shows that rising services prices that contrast with falling goods’ prices can be explained by it being hard to further increase productivity in services. At least until AI and robotics revolutionize services, similar to how the Industrial Revolution revolutionized goods.

Max Roser’s Air Pollution: Does it Get Worse Before It Gets Better? and Andrew McAfee’s More from Less plot the progress we’re making on pollution. CO2 and other Greenhouse Gas Emissions hints at the remaining problems.

In Economics of Violence, Gary Shiffman suggests that “access to increasingly larger markets, facilitated through information technology, the World Wide Web, and social media, creates more transnational opportunities for deception, coercion, and violence.”

Towards 2030 Without Poverty by See Martijn Lampert.

Stubborn Attachments by Tyler Cowen.

Meditations on Moloch by Scott Alexander.

Comparative Ecology by Eric Drexler’s and Mark S. Miller .

Our World in Data by Max Roser.

This positive development is larger than economic growth alone and should be attractive to other popular approaches for evaluating progress. In Development as Capability Expansion, Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen introduces capability methods for evaluating human development. These are not tied to GDP alone but measure how many valuable opportunities a person is capable to take advantage of in their environment. His priority capabilities include literacy, health, and political freedom, all of which are on the rise.

Markets and Computation: Agoric Open Systems by Mark S. Miller and Eric Drexler.

It is widely understood that in the absence of money, trade would be limited by the double coincidence: For a barter to happen, I must have something that you want and you must have something I want. But money by itself doesn’t solve the problem. Perhaps the package delivery clerk happens to have a car he wants to sell and I happen to need a car just like it and am willing to pay just the right amount. We will never discover this because I am there to ship a package and we never get into that conversation. The collection of things we have and want is so complex that we can’t talk to every agent that we encounter about what we can do for each other. Institutions help me, with all my specialized knowledge about what I want, to find others wanting complementary things.

Institutions as Abstraction Boundaries by Bill Tulloh and Mark S. Miller.

Markets and Computation: Agoric Open Systems by Mark S. Miller and Eric Drexler.

The Constitution of Liberty by Friedrich Hayek.

Contracts for Components by Bertrand Mayer.

User Interface: A Personal View by Alan Kay.

Development of Logic Programming by Carl Hewitt.